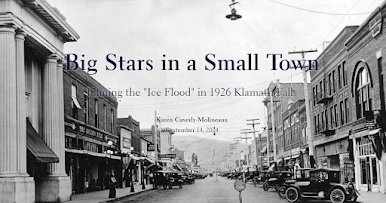

In early 1926, Universal Studios filmed a silent feature-length movie called Crashing Timbers (later released as The Ice Flood) in the small town of Klamath Falls, Oregon. The Ice Flood starred well-known Hollywood actors Viola Dana and Kenneth Harlan, with child actor Billy Kent Schaeffer, and was directed first by James Spearing, but finished with George B. Seitz (reason for change unknown). The Klamath Falls community saw social, economic, and mild infrastructure impacts as a result of the Universal Studios’ visit to the town during January and February 1926.

The silent film era provides a unique view for historians of the arts, entertainment, and culture that existed in the Progressive Era America. Studies estimate seventy to ninety percent of silent feature-length films produced between 1912 and 1930 have been lost, yet The Ice Flood film survives. There are no remnants of the movie’s filming found in local archives or at the museum, except for a dvd of the movie and historical newspaper articles from 1926 and 1927. People who would have first-hand accounts of the event have long since passed, and there is no indication that their descendants have anything to offer on the topic.

Reports on the topic over the years also do not indicate its significance for the community in and around Klamath Falls, both during the time of film production or when the movie was released and shown, a year after filming. A lone scholarly article written in 2005 by archivist and historian Bill Alley notes missing information in the reconstruction of the historical narrative.1 The Ice Flood was originally released to audiences in 1919 under the title The Brute Breaker, a story written by author Johnston McCulley - creator of the acclaimed film hero Zorro. There are no copies known to exist of that movie, however.

My study of this surviving historical silent film has been guided by the following driving questions: What new information has been found on the topic? How did the production crew and cast interact and impact the town? Can the reasons for The Ice Flood’s survival and The Brute Breaker’s demise be found?

Primary sources such as newspaper and magazine articles, newsletters, Library of Congress documents, and the movie itself can be used to construct an updated narrative of the topic and fill gaps of missing information noted in Alley’s 2005 article. Secondary sources that describe studies of silent film and provide explanations of silent film’s significance for historians can serve as a baseline of what is known, and what is new discovery on the topic, can also be used in answering driving questions - as well as explain the significance of surviving silent films.

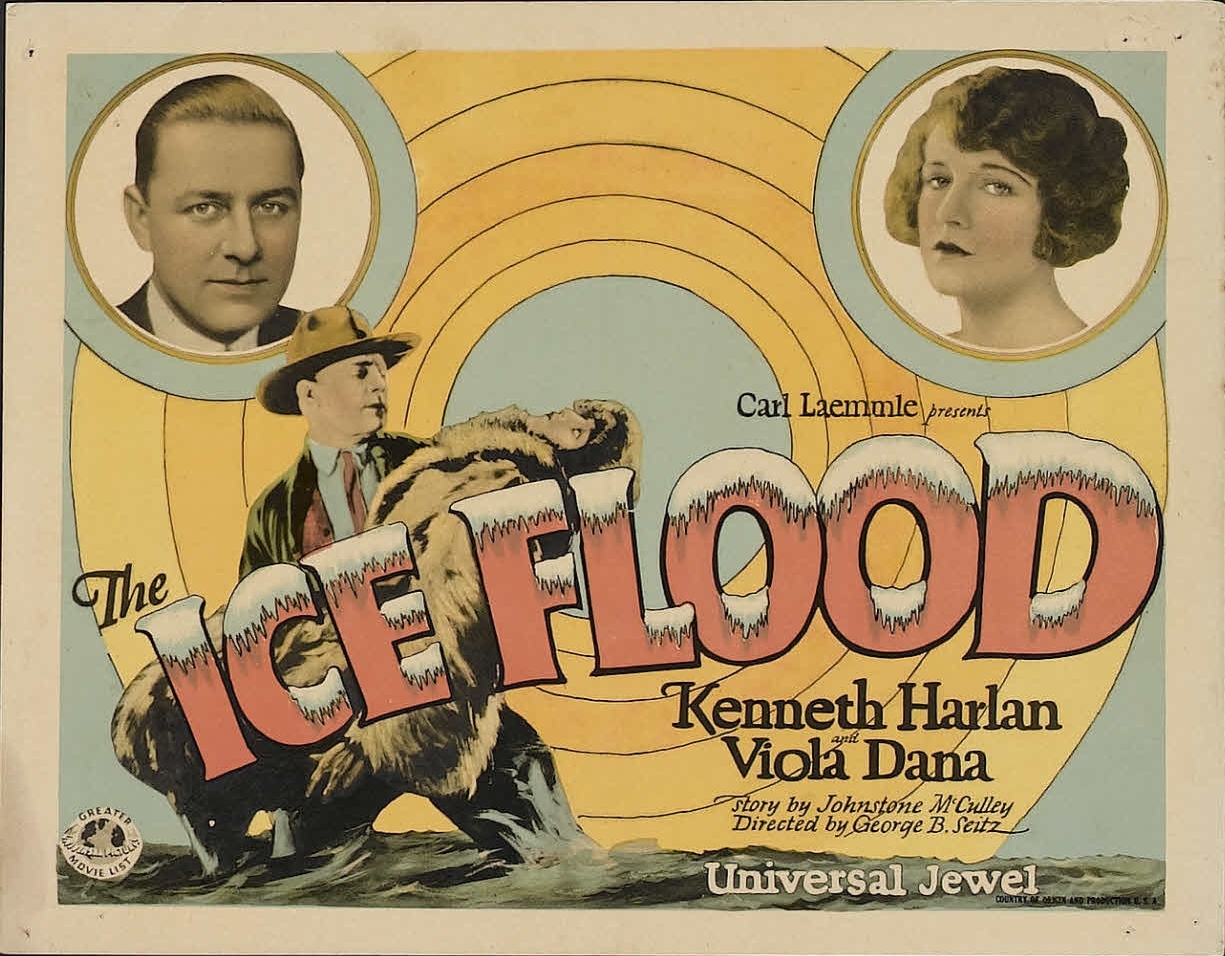

I also tracked down lobby card reproductions of the movie and had them printed in the traditional size of 14 inches long by 11 inches tall, on lightweight poster board. (Thank you Shortrunposters.com for an awesome job!)2 An article in Smithsonian Magazine explains that “lobby cards were displayed in sets of eight or more in the lobbies of movie theaters. The first card typically displayed a film’s name and crew, which was followed by scene cards that gave viewers a glimpse at the plot.”(see image 1, 2, & 3).3 I didn’t know that they were produced in sets of eight - this is how many I was able to find, so I must have a complete set!

Image 1, lobby card displays film’s name & crew.

Image 2, lobby card shows scene from movie. Image 3, lobby card shows scene from movie.

The article adds that sometimes lobby cards “are the only surviving evidence of a film’s existence, as so many early films have been lost or destroyed,” “can add nuance to contemporary film scholars’ understanding of the early days of cinema,” and they “revealed the importance women played in the silent film industry, both in front of and behind the screen.”4

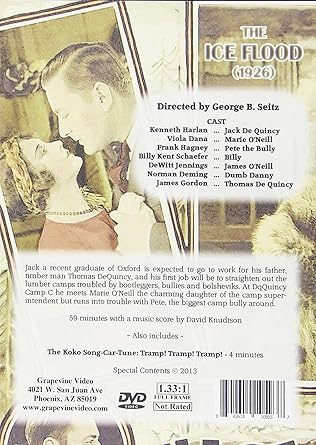

I also tracked down and purchased copies on dvd of the film, one by Grapevine Video and the other by Alpha Video (see images 4 & 5). There is another version out there done by the now out-of-business Sundance Films. One other copy can be found on YouTube that is courtesy Variety Films (I have watched this one), and along with the two dvds I bought, will be my next endeavor of comparing and noting differences of the copies. Here's the link to the YouTube copy: https://youtu.be/vp4RMloPHlk?si=5Rz9Yo6KjatbjRk9.

Image 4, Grapevine Video’s 2013 copy Image 5, Alpha Video’s 2017 copy

One last resource I have constructed on the topic is an oral history interview with Kurt Liedtke. He is the local film guru, as he is the former executive director of Klamath Film. He's an independent filmmaker and he worked for over a decade in Hollywood in various roles in film and music production. Kurt has a vast knowledge of film origins, and particularly of the silent film industry and era.

There are parts of my interview with him where he speculates on some aspects of The Ice Flood. After we completed the interview we were able to chat, and I was able to clarify and inform him on where the movie was filmed (close to McCollum’s Lumber Mill on the Klamath River, around 6 miles past Keno, Oregon), that the Altamont dance pavilion was the site for indoor filming and there was an electrical substation constructed to accommodate power needs, and that the entire film was re-shot at Universal City except for the outdoor scenes. Here's the link to that interview: https://youtu.be/oI2lL-rHto0.

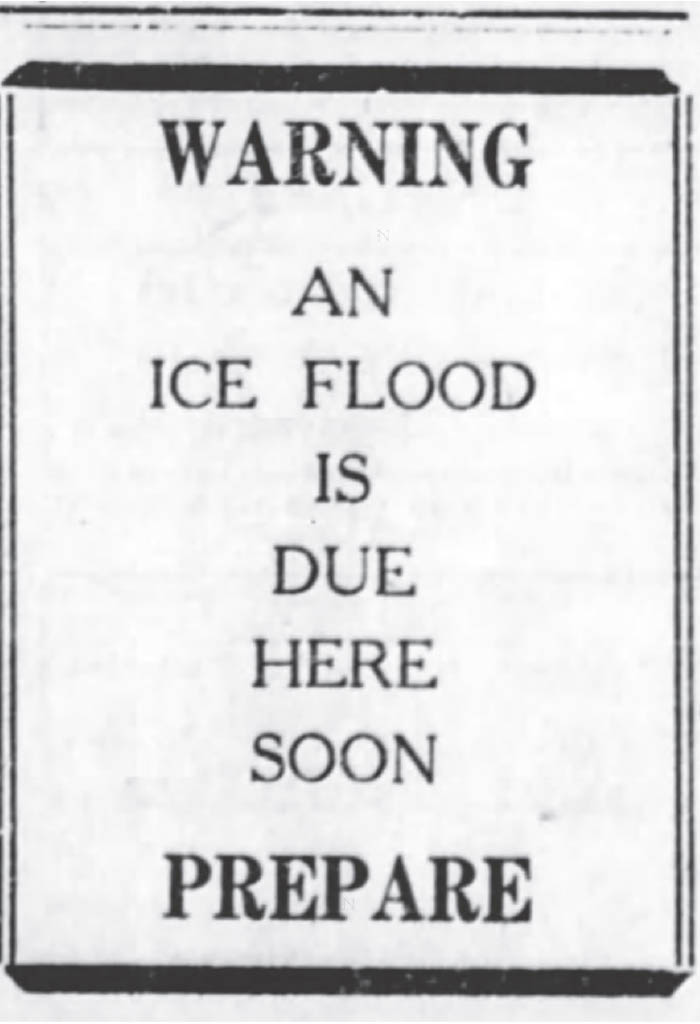

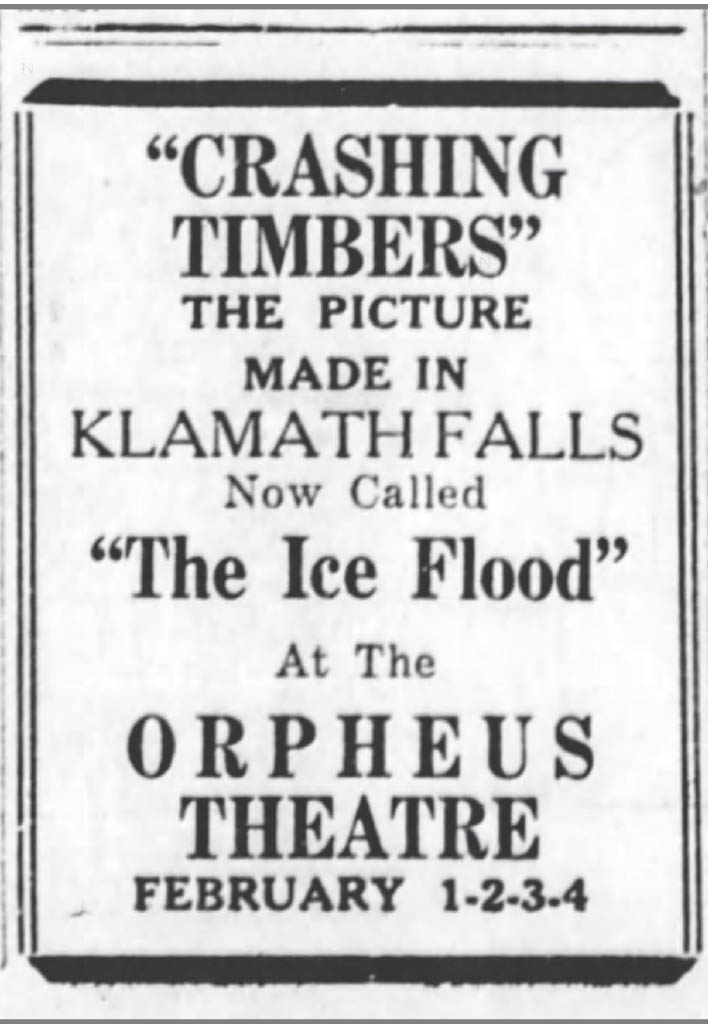

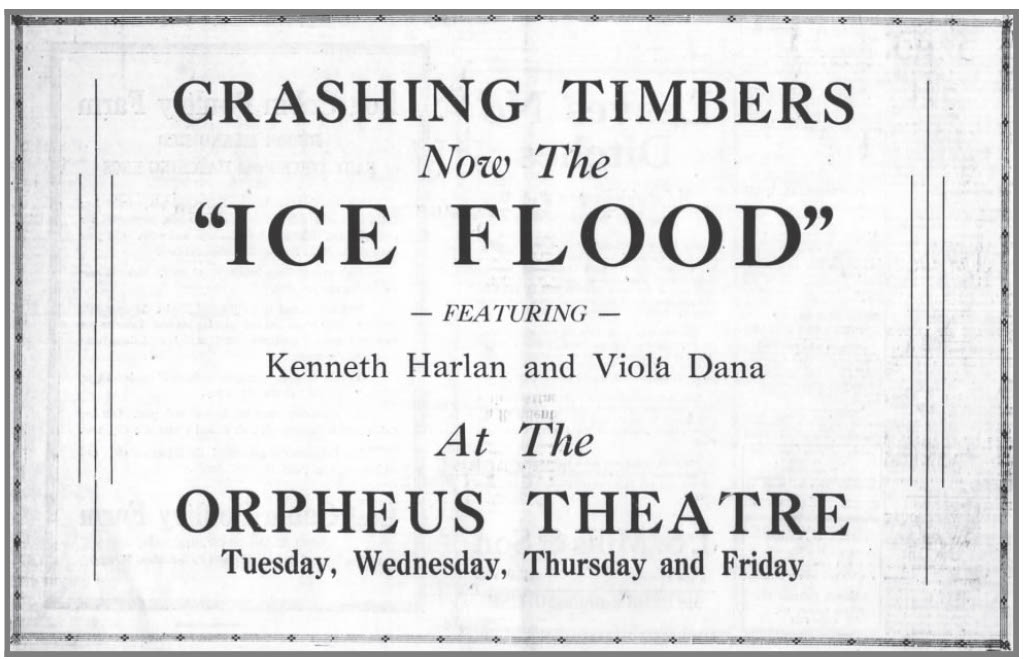

I was able to find the missing information Alley noted in his article during my research: He claimed that the film was never shown in Klamath Falls,5 but newspaper reporting contradicts that claim (see images 6, 7, & 8).6 Alley does note that he examined back issues of the Evening Herald, and did not mention looking at issues of the Klamath News - Klamath Falls’ other newspaper at the time. Alley figured that mixed reviews, and ones that were “not encouraging…might explain why it was never shown in Klamath Falls.”7

Image 6, Klamath News, Jan. 25, 1927, p. 8 Image 7, Klamath News, Jan. 27, 1927, p. 8

Image 8, Klamath News, Jan. 30, 1927, p. 6.

__________________________________________

Notes:

1. Bill Alley, “Crashing Timers, Ice Floods, and Movie Stars: Universal Studios Comes to Klamath Falls,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 96, no. 4 (Fall 2005): 181-186, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40491874.

2. Located in Nashville, Tennessee, https://www.shortrunposters.com/.

3. Ella Feldman, “See the Stunning Lobby Cards Keeping Silent Movies Alive: Thanks to a Collector, Thousands of Lobby Cards from the Silent Film Era Will Soon Be Digitized,” Smithsonian Magazine online (Oct. 19, 2022), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/tons-of-silent-movies-have-been-lost-to-time- lobby-cards-help-some-survive-180980943/.

4. Ibid.

5. Alley (Fall 2005), 185-186.

6. A pre-showing announcement appeared in the Klamath News on Jan, 25, 1927 stating “WARNING An Ice Flood Is Due Here Soon PREPARE,” and according to Klamath News ads on Jan. 27 & 30, 1927 the picture was being shown at The Orpheus Theater on Feb. 1-4. Two other articles in the Klamath News appeared on Jan. 30 & Feb. 1, 1927 that announce the upcoming screening of the film at The Orpheus.

7. Alley (Fall 2005), 185-186.